Not “Under Control”

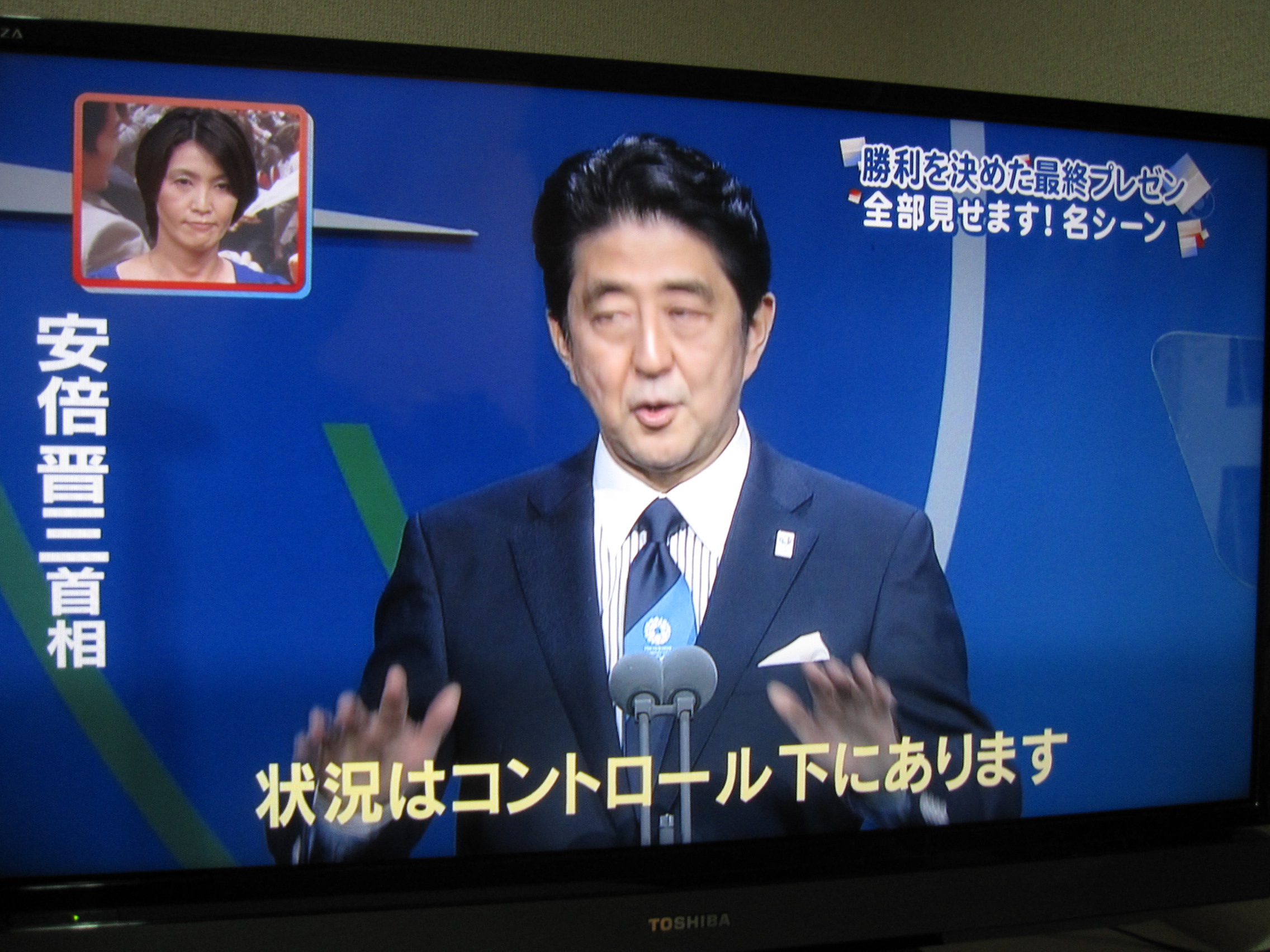

FUKUSHIMA, 1 Oct. 2013. I listened to Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s speech at the 125th IOC Session in Buenos Aires on 8 September in the city of Fukushima, where I work. When I heard him declare that the situation of the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Fukushima is “under control,” I wondered what possible basis he could have had for such a statement.

Prime Minister Abe declares to the members of the IOC that the nuclear crisis in Fukushima is “under control.”

No one has confirmed the state of the nuclear fuel that melted down in the Daiichi plant’s destroyed No. 1, 2 and 3 reactors. Nor is it possible to know the extent to which the radioactivity of the meltdown continues to affect underground water. According to one estimate, the amount of radioactive material that flowed out of the plant into the ocean during the approximately one month following the explosions March 12-15 is between 3,500 and 5,000 trillion becquerels. Even now, some 400 tons of groundwater is flowing daily into the reactor buildings [http://mainichi.jp/select/news/20130905k0000m040099000c.html]. It was reported on 18 September at the IAEA Scientific Forum that the amount of radioactivity released into the ocean from the base of the reactor shelters is over 60-billion becquerels per day [http://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXNZO59888260Z10C13A9CR8000/].

Yet the first time Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO), which operates the Daiichi nuclear power plant, admitted that seawater was being contaminated was the day after the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) emerged victorious in the July 21st general elections. Plenty of experts have been expressing urgent concern about the problem ever since the time of the accident. Japanese are well aware of the collusion between TEPCO and the LDP, which has backed the nuclear power generation policy from the outset, and people are increasingly disgusted by the failure of the LDP and the mammoth power company to consider the welfare of the Japanese people.

The Uprooted and the Untested

Driven from their homes by the power plant accident, some 150,000 citizens of Fukushima prefecture continue to live uprooted lives. More than 1,500 deaths have been recorded related to the nuclear power plant accident (as of 30 September), including the death of elderly and ill evacuees whose health deteriorated in their places of evacuation and suicides resulting from dreams destroyed and daily hardships suffered. So far, 18 children have already been diagnosed with thyroid cancer (as of 20 August). The rate of thyroid cancer among children under ordinary circumstances is only 1.3 per 100,000, and only some of the 360,000 children who are targeted for medical examination have been tested so far. And yet, in response to questions after his speech, Prime Minister Abe stated that, “there are no problems with health now or in the future.”

Fukushima prefecture’s most pressing issues are how to secure safe supplies of food for its residents and how to restore local agriculture, which is the key industry of the region. At present, however, farmers have been planting crops and shipping produce to market without knowing the extent to which their rice fields and orchards have been contaminated by radioactivity. If they stop cultivation, the government and TEPCO will withdraw payment of compensation funds. Farmers are plagued by the question: “Can I let my children or grandchildren eat the crops that I have produced?”

Particularly owners of land in contaminated areas and activist organic farmers have taken matters into their own hands. The government, they say, “doesn’t play fair, is secretive, hoards and conceals information.” Citing distrust of the government, some farmers have begun to check radiation levels themselves. In Fukushima prefecture not only the issue of radioactivity exposure but government compensation as well is divisive. Differences of as much as 10 million yen in compensation have created serious rifts among local citizens. I remember hearing one farmer living in a high-dose area say that “even though we try to build solidarity in a region toward solving the problems, the way things are done seems to pit residents against each other.”

The perpetrators of the accident are TEPCO, whose power plant spewed out radioactive cesium of a quantity more than 167 times that resulting from the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and the government, which backs the nuclear power generation policy and declares that there was “no accident.” While such denials continue, there has been much ado over “damage due to rumor,” casting those who do not purchase Fukushima-cultivated produce as the victimizers and the hardworking local farmers of the Tohoku prefectures as the victims. In fact the consumers and the producers are all victims. The value of agricultural production, which had stood at 232 billion yen in the year before March 11, 2011, dropped to 170 billion yen the year of the disaster, and its recovery is not yet in sight.

Bigger than Anger

Outside Fukushima and outside Japan, people from Fukushima are asked, “Why don’t you just leave?” Those who deem the effects of radioactivity as a threat, and are able to get away in terms of work and economic situation, have already left Fukushima. But the Tohoku region as a whole, and of course Fukushima prefecture as part of it, has a very long history going back at a thousand years. Rich agricultural land has been handed down for generations, more than 10 generations in some villages. The farmers cannot easily make up their minds to abandon land they have nurtured for generations with the same tender loving care with which they raise their children. This is one major difference from Chernobyl in the Soviet Union where the land belonged to the state.

They may also be asked “Why didn’t you get angry?” One farmer admits: “The problem is too huge. And we are desperate just to deal with the problems we were facing day to day—we can’t afford to get angry.” Historically Fukushima is a region where the popular rights movement was vigorous. Nature can be quite severe in Fukushima, so it is also the place where farmers voluntarily joined forces to overcome their problems, the place where the agricultural cooperatives now established all over Japan started out. In other words, even though people may not be showing anger, it is a region where new, very fundamental movements may well be born from among the people.

Innovation and Pragmatism

On 1 October 2012, a “Soil Screening Project” was launched as a collaboration by local agricultural (nokyo) and consumer (seikyo) cooperatives, along with Fukushima University. I took up a post in the office of this project at that time, now just about a year ago. Tests of level of contamination at three points in each paddy or orchard are tested using a Belarus-made device called the “Rocket” that costs 1.9 million, and the figures are used to compile a map of radiation substance distribution. Just as when we begin to treat a human patient for illness by identifying the symptoms and condition, this project makes its objective “grasping all the conditions.”

Testing the radioactivity of rice paddies is done betweenharvest time and planting the following spring, namely between October and April. Orchards are measured during the summertime.

One other major challenge is to remove the vague sense of unease and distrust that has spread throughout society since the accident. The “Soil Screening Project” is addressing this challenge by having volunteers who are sent to Fukushima as consumer representatives by cooperatives from around the country help with the work as well as see the figures first-hand for themselves and convey an honest picture to the rest of the country. This is the kind of innovation and pragmatism that can be achieved by the private sector.

There are about 38,000 rice paddies and orchards (the main thrust of the Project) in the JA Shin-Fukushima(the only “nokyo” out of 17 in Fukushima prefecture running the Project) area, meaning there are about 114,000 points to be tested. Each team using one of the “Rockets” surveys the soil of 25 to 30 rice fields or orchards per day, and 4 or 5 teams are conducting surveys daily. By comparison, there are as few as 31 testing points that the government uses as a basis for its assessment of safety.

Fukushima’s winters are bitter cold and the heat in the Fukushima basin is intense in summer. The stalwarts who sustain this work despite the fluctuating weather are three natives of Fukushima in their fifties and four on-site staff in their twenties. These are the ones who have really distinguished themselves in this project. The liaison between the agricultural and consumer cooperatives—which is the ideal form of collaboration between cooperative groups—is at once unprecedented and inconspicuous.

The seven staff members who have tested all of approximately 10,000 orchards in the JA Shin-Fukushima area as of 3 October 2013.

Priorities and Promises

We have nothing against having the Olympics in Japan, but we cannot help comparing the 600 billion budget Prime Minister Abe announced had been drawn up for the Olympics with the 47 billion he announced would be invested in cleaning up the radioactivity contamination. In the same IOC speech, Naoki Inose, governor of Tokyo, boasted that Tokyo had a previously established fund of about $4.5 billion (about 450 billion) to support preparations for the Games. Already, materials and manpower are in short supply for the continuing 2011 disaster recovery effort because they are being shifted to Olympic-related projects.

The cost needed to operate the Soil Screening Project, about $200,000 (about 20 million) per year, is now being covered by JA Shin-Fukushima. JA has tried to persuade TEPCO to pay for it as a form of compensation, but to no avail. They have refused to pay, saying that there is no framework for compensation of that kind.

We also note that debate is currently going on in the Diet about a “specified law for secrets protection.” This bill proposes that what the government judges should be kept secret must be kept secret. If this were to be passed into law, it could be used to silence individuals or the media.

Telling lies in order to win selection of the site for the 2020 Games is a serious violation of the Olympic spirit. If we feel that the truth is not being told, how can we promise our children “dreams,” “hope,” and a “future”?

(Translation by Lynne E. Riggs)

2013/11/11

事務局